By Patrick Reynolds

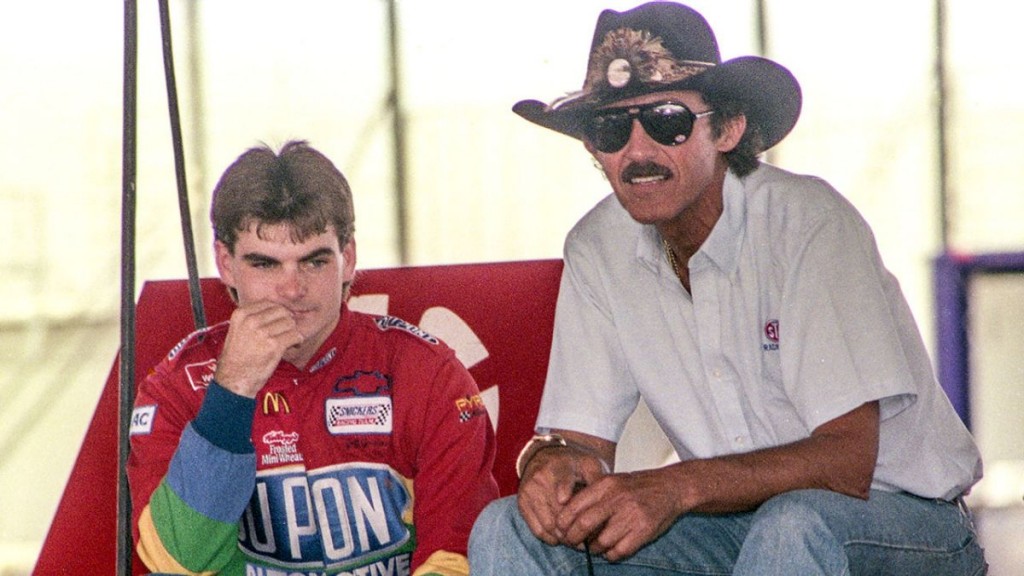

For me, Jeff Gordon at NASCAR’s highest level begins with Richard Petty.

The Daytona 500 became synonymous with Petty and his seven wins. Gordon is a three-time 500 victor and also enjoyed great success at the superspeedway located a few miles from the beach where the area racing began.

When I first became an auto racing fan in the 1970s, and my interest reached beyond my local and regional stars, Petty was my favorite driver on the national level. I wore the day-glow orange and unique-blue hats. My t-shirts had STP screen printing. School art drawings were of the number 43 roaring through a turn. Petty was ‘my guy.’

In the fall of 1991 Petty made an announcement that had been anticipated for a few years. He would be stepping out of the driver’s seat and 1992 would be his final season behind the wheel of a stock car.

These same years would be the liftoff to Gordon’s NASCAR career and the baton would be passed from Petty, although at the time none of us knew those motorsports constellations would be lining up.

At that point in my life I had not made the transfer to earning a paycheck as an auto racing professional. I was employed in a regular 40-hour per week job, yet spent nearly every night working on friends’ short track cars. Friday and Saturday nights were dedicated to local speedways. Sunday afternoons I was a fan in front of my TV watching racing. I viewed nearly every then-Winston Cup race and pulled for Petty. When he announced his driving retirement I made it a point to see him off as a loyal fan.

In 1992 I attended Petty’s final Daytona 500, both Dover races, and his last one ever- The Hooters 500 at Atlanta Motor Speedway.

Petty kicked off the Fan Appreciation Tour in 1992 with his final Daytona 500. Davey Allison won by a few car lengths over Morgan Shepherd. The race suffered through its version of “the Big One†when Ernie Irvan, Bill Elliott, and Sterling Marlin came together while racing three-wide for the lead just beyond the race’s halfway point. The multi-car crashed was triggered and collected, among others Dale Earnhardt and Petty. Earnhardt made the most of a battered car and came home ninth. Petty salvaged a 16th-place finish despite his own damage.

A wonderful championship battle had formed during that year through the Latford-points system, and not a credibility-decaying Chase in sight. Bill Elliott, Alan Kulwicki, and Davey Allison were close title combatants as the Atlanta finale was set. Harry Gant, Kyle Petty, and Mark Martin lurked as mathematical possibilities. Combining this with an emotional Petty sendoff equaled a race weekend where the actual excitement realistically exceeded the hype.

Atlanta’s weekend produced many sidebar stories. Loy Allen won the ARCA Saturday preliminary race in a contest dominated by Mike Wallace. Rick Mast won his first career pole. Young Busch Series race winner Gordon was making his first Winston Cup start in a new Hendrick Motorsports ride.

I wrote the previous paragraph purposefully. At the time of the race, Gordon’s first-career Cup series start was noteworthy, however it equally lined up with several other stories that filled the racing news. At that point in time, there was considerable speculation on Rick Hendrick’s choice for his third driver to join Ricky Rudd and Ken Schrader as Cup teammates.

Gordon was known to auto racing followers. His USAC notoriety was watched by many on ESPN’s Thursday Night Thunder. I was a regular viewer and caught him in the summers of 1988 through 1990. He made his first NASCAR start in Rockingham’s fall Busch Series race in 1990 and surprised with an attention grabbing second-place qualifying run. An early crash ended his day prior to the race’s first pit stop.

Gordon moved to NASCAR’s Busch Series full time with Bill Davis Racing for 1991 and 1992. To kick off his first season at Daytona- the track Petty was so synonymous with- Gordon did not qualify for the Goody’s 300. The Davis Ford did not generate the speed in time trials to crack the 43-car lineup. He did manage to successfully make the year’s remaining races and finish 11th in the championship standings.

In March of ’92, Gordon claimed his initial Busch Series win at Atlanta. A few months later, came the surprising announcement of his future with Hendrick Motorsports. Gordon has shown competitive talent, however moving him to NASCAR Winston Cup competition left many scratching their heads.

The backstory is that Hendrick noticed how loose Gordon’s car drove through the Atlanta corners during the 300-mile win and impressed the team owner with his car control ability. That led to interest and then signing of the young driver.

Gordon swept the 1992 Series’ races at Charlotte and ended the year with three wins. General consensus among the bench-racing crowd was that Gordon was talented, but was biting off way more than he could chew with the jump to Cup.

Gordon’s Atlanta Winston Cup debut showed promise. Among Petty’s emotional finale and fiery crash out of the race and the tight Cup title slugfest, I paid attention to Gordon during the event. From my grandstand seat, he kept pace with top-20 cars and ran impressive lap times. However, crash damage eventually led to his race retirement.

The stories that made headlines were the razor-thin points battle between race winner Elliott and champion Kulwicki, Petty’s crash and farewell, and Allison’s crash, title loss, and graceful attitude. Buried in the statistics was Gordon’s 31st-place finish. At that time, it was just as notable as Bobby Hillin’s 30th-place effort right ahead of him.

The start of 1993 would prove the doubters- me included- wrong.

When February finally rolled around, Gordon time trialed 11th for his first Daytona 500, which gave him the sixth starting spot for the first 125-mile qualifying race. On the 125’s pace laps, a competitor’s spotter was heard as telling his driver over their radio something to the effect of keep your eyes on that rookie. He is about to be taught a lesson.

On this sunny, Thursday afternoon the NASCAR world was about to get a glimpse of the potential that Hendrick saw.

Sixth was the lowest Gordon would run over the 50 laps. He drafted with Schrader, Kyle Petty, Rick Mast, and passed Elliott for the lead before the halfway mark. He led the rest of the way with Elliott on his bumper for the win… make that a shocking win.

Jeff Gordon was not Jeff Gordon and Hendrick Motorsports was not Hendrick Motorsports… yet.

Gordon showed the 125-mile win was no fluke. Come 500 Sunday, Gordon led the first lap and made his presence known all day. He was right in the mix of the famous Dale and Dale show with a fifth-place finish on the final lap scramble that saw Jarrett pass Earnhardt for the win. Geoff Bodine was third, Hut Stricklin fourth, and then Gordon.

Monday morning water cooler talk included the observation that if Gordon had more experience, he could have won the Daytona 500 in his first try.

He moved on through his rookie season with one impressive run after another. Gordon qualified well, led laps, and had strong finishes. However, the 1993 year was not all one of glory, as wrecks also piled up also while Gordon learned where the limit was in the heavier cars with higher horsepower than the Busch Series.

I was introduced to Gordon in April of that year in Charlotte, NC. I visited the area for the first time and was looking for job opportunities with NASCAR teams and places to live. I met with fellow D.I.R.T. Modified crew member Shawn Parker who was then employed within Hendrick Motorsports and changing rear tires on Gordon’s number twenty-four.

Parker met me for dinner and we joined another small group that he knew from Hendrick, including Gordon. There was roughly a half-dozen of us at the table and we ate, talked, laughed, and shared stories. Gordon was truly just one of us and not any kind of celebrity. He blended into our group, and the whole restaurant like all of the other customers. I left with the impression that Gordon and the Hendrick folks were no different than all of my Modified racing friends- just good racing people.

My personal life put off the move to Charlotte for several years, but that is a story for another time.

Gordon continued impressing through to a 14th-place championship finish and Rookie-of-the-Year honors. Something else was also happening. National media was paying attention to this young driver named Jeff Gordon.

I do not mean ESPN’s Sportscenter or TNN’s Raceday. I mean Entertainment Tonight and People Magazine. Gordon was 21, good looking, well spoken, and fast. There was no other top level NASCAR driver with all of those qualities. That appeal momentum would build over the coming years.

The 1994 season brought his first two Cup wins and both were memorable.

Crew chief Ray Evernham made a well-known “Two Tires†call for the final pit stop under green during the Coca-Cola 600 which led to Gordon’s first career Cup victory and a teary-eyed winning driver.

Gordon’s second-career Cup triumph was celebrated later that summer in the inaugural Brickyard 400 held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. NASCAR’s first race at the famed facility was an immense and historic day for both the winner and the sanctioning body.

As a race fan I was picking up cheering for Gordon. My Petty hats were still safely kept, but now Gordon t-shirts were making their way to my collection. Bright colors for a driver I pulled for were worn once again.

I was thrilled there was actually a driver who could give Earnhardt a run for his money. The late 1980s and early 1990s were the strongest points in The Intimidator’s career. Many good drivers simply could not run with Earnhardt. Gordon was one who finally could.

On paper, the pair was very opposite. One had a native southern accent, a black car, and an age in his 40s. The other, a California and Indiana transplant with a rainbow-themed paint job and 21 years old. They were polarizing and mixing it up more and more on Sunday afternoons. They were a fantastic pair for the sport’s energy and attention.

Seven more Victory Lane appearances and Gordon’s first championship defined 1995. That mainstream media attention NASCAR had not seen before kept snowballing. David Letterman, The Tonight Show, and Good Morning America welcomed the young champion. He was carrying stock car racing to a new level. Much like Petty did in the 1960s and 70s, Gordon was now doing in the 90s. The right driver at the right time was elevating the sport.

Jeff Gordon was now Jeff Gordon. Hendrick Motorsports was now Hendrick Motorsports.

Gordon’s 93 series wins and four titles are well-documented through the next twenty years as his Hall of Fame career came to an end in 2015.

Some of my younger contemporaries have not seen a Cup race without Gordon. This will be a strange feeling for them. The same feeling a generation ago felt when NASCAR waved that 1993 Daytona 500 green flag without King Richard in the field.

Jeff Gordon and NASCAR- for a younger demographic, the two are synonymous. Gordon’s meaning and impact on professional stock car racing, is the same as the more experienced fan base felt about Richard Petty and the sport. When you thought of NASCAR, you thought of the other.

Now we come to the 2016 Daytona 500- a Daytona 500 without Jeff Gordon. When was the last time a Daytona 500 was run without him? Right where this story began. It was the last Daytona 500 with Richard Petty. Since Allison drove Robert Yates’ Ford under the checkered flag on that overcast day, every Daytona 500 has been held with Gordon… until now.

From Fred Lorenzen, to Richard Petty, to Dale Earnhardt, to Jeff Gordon, NASCAR had its superstars that helped raise the sport to another level.

Now NASCAR begins an era without a Petty or a Gordon, in a time where the sport could use more Pettys and more Gordons. The fastest-growing sport in in the 1990s, in which none of us could honestly view where the ceiling would be, is in 2016, at best- flat.

Who will be that next Jeff Gordon? By that, I do not mean a driver who wins races and championships. NASCAR has those, and that does not necessarily translate into ‘moving the needle.’ I mean a driver who carries the sport beyond the confines of its fan base and further into mainstream America- someone who is polarizing. That is a daunting challenge and responsibility.

We did not know this as the field roared under the 1993 Daytona 500 green flag for the first time without Petty and with Gordon. Time unfolded and we experienced the NASCAR magic.

The 2016 Daytona 500 is at our doorstep. Who is next?

Patrick Reynolds is a former professional NASCAR mechanic who hosts Motor Week LIVE! Mondays 7pm ET/ 4pm PT on www.racersreunionradio.com